Anyone looking for ideas for new products and services need look no further than the World Economic Forum, Global Risks Report. Each year a group of experts get together and work out which risks are the most threatening to our existence.

Once upon a time it was pestilence, plague, the weather and other natural disasters such as tsunamis, hurricanes and tornadoes. They have not gone away, but some very clever people have found solutions to these problems, and turned them into business opportunities.

The first modern sewage systems owe their existence to cholera outbreaks in the 1830s, 1840s amd 1850s in London, United Kingdom that killed tens of thousands, as well as the Great Stink of 1858 which resulted from the overpowering smell of excrement in the Thames River. A huge underground network of sewers was built under the city to pipe it away. Later other European cities followed suit, as did cities in Northern America. Today sewage is a trillion dollar business world-wide.

Safe water supplies using chlorination really only got going in 1905, after a typhoid outbreak in Lincoln, England. The first US installation was Boonton, New Jersey in 1908. Another trillion dollar business.

Until the 1800s, millions of people every year died from infections, most of then preventable deaths. It was only when we realized that germs were the basis of disease and that antibiotics such as penicillin could kill them, that most of us began to survive, not one, but multiple infections, routinely. We have Pasteur, Lister, Fleming and Florey to thank for these discoveries. Sadly, millions in developing countries still die from diseases every year that are preventable in the west. Yet another trillion dollar business. However, our war on germs has caused some bugs to mutate and develop resistance. Think golden staff and TB.

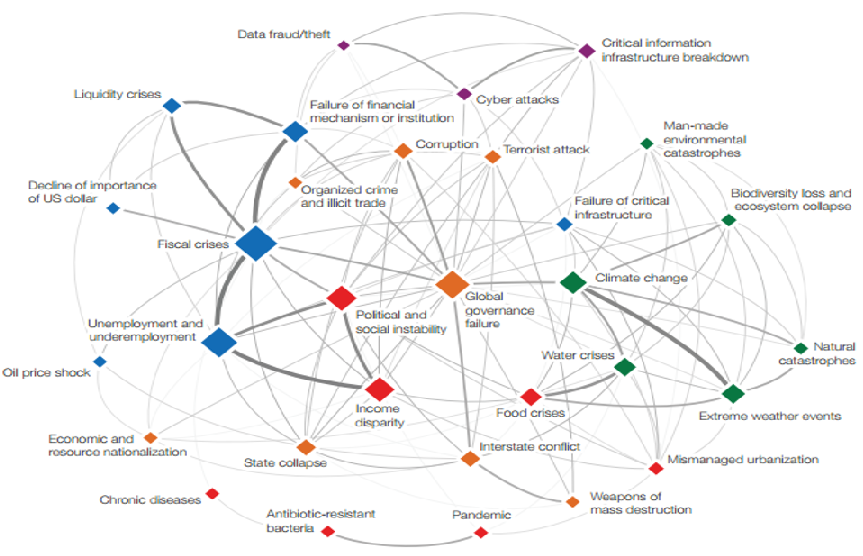

Here’s a list of the top 31 risks according to the 2014 Global Risks Report, and an image from the report (above) which shows the interdependencies between the risks, and how they can impact each other:

- Fiscal crises in key economies

- Failure of a major financial mechanism or institution

- Liquidity crises

- Structurally high unemployment/underemployment

- Oil-price shock to the global economy

- Failure/shortfall of critical infrastructure

- Decline of importance of the US dollar as a major currency

- Greater incidence of extreme weather events (e.g. floods, storms, fires)

- Greater incidence of natural catastrophes (e.g. earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions, geomagnetic storms)

- Greater incidence of man-made environmental catastrophes (e.g. oil spills, nuclear accidents)

- Major biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse (land and ocean)

- Water crises

- Failure of climate change mitigation and adaptation

- Global governance failure

- Political collapse of a nation of geopolitical importance

- Increasing corruption

- Major escalation in organized crime and illicit trade

- Large-scale terrorist attacks

- Deployment of weapons of mass destruction

- Violent inter-state conflict with regional consequences

- Escalation of economic and resource nationalization

- Food crises

- Pandemic outbreak

- Unmanageable burden of chronic disease

- Severe income disparity

- Antibiotic-resistant bacteria

- Mismanaged urbanization (e.g. planning failures, inadequate infrastructure and supply chains)

- Profound political and social instability

- Breakdown of critical information infrastructure and networks

- Escalation in large-scale cyber attacks

- Massive incident of data fraud/theft

If you take a close look at the kinds of dangers we now most fear the most, they seem to be breakdowns/failures in the systems we humans have created. They are also mostly in the realm of governance. In the past governance has been the responsibility of our political leaders. And as any avid student of systems thinking will tell you, governance innovation, or the ability to redesign and influence the adoption of the rules of the system, is much more powerful than either product or service innovation.

Here’s a workshop to think about an opportunity creation approach to risk:

Workshop:

1. Brainstorm a list of risks that you, your community or your business face in a normal year. An abnormal year.

2. Choose 5-6 of the most likely or risky events with the potential for the most serious consequence for you, your community or business, and estimate the likely impact, damage etc.

3. Thinking about the 5-6 most damaging, chaotic or disruptive risky events, what if any solutions (technology, services, redundancy, forecasting, early warning, rapid response etc.) are easily or readily available to you. Make a list of the risks and how you can mitigate/reduce or bounce back easily.

4. Thinking about the risks that you cant easily resolve, especially those that have rapid knock on (chaotic effects) what could you do differently to deal with those risky events? What new disciplines might you explore for new and better solutions, or what multiple disciplines and new knowledge from those disciplines could you bring together to deal with the risk in a new way?

5. Thinking about the World Economic Forum Risks Report list of risks, how could you, your business or your community use its expertise/new knowledge/experience to prevent, mitigate, or rapidly respond to/damp down the effects of a risk, and turn it into a product or service for others to buy.

6. Whats a problem/issues you are experiencing in your community which has defied all efforts to make an improvement? In what ways might you be able to deal with this differently and become an expert in its resolution, then supply that service to other organizations or communities?